Bitwise operations and related concepts

Two’s complement

Let’s look at 4-bit integers. Tiny, but useful for illustration purposes. Since there are four bits in such an integer, it can assume one of 16 values. What are those values? The answer depends on whether this integer is a signed int or an unsigned int. Signed integers can represent both positive and negative numbers, while unsigned integers are only non-negative.

0000 0

0001 1

0010 2

0011 3

0100 4

0101 5

0110 6

0111 7

1000 -8

1001 -7

1010 -6

1011 -5

1100 -4

1101 -3

1110 -2

1111 -1I’m curious if there’s a reason -1 is represented by 1111 (two’s complement) rather than 1001 which is binary 1 with first bit as negative flag.

In computers, integers are stored in two’s complement form. In two’s complement representation, computers can treat addition of positive and negative numbers equally, eliminating the need for separately designing special hardware circuits for subtraction operations, and avoiding any ambiguity regarding positive and negative zero.

Say you have two numbers, 2 and -1. In your “intuitive” way of representing numbers, they would be 0010 and 1001, respectively. In the two’s complement way, they are 0010 and 1111. Now, let’s say I want to add them.

Two’s complement addition is very simple. You add numbers normally and any carry bit at the end is discarded. So they’re added as follows:

0010

+ 1111

= 10001

= 0001 (discard the carry)0001 is 1, which is the expected result of 2 + (-1). But in the “intuitive” method, adding is more complicated:

0010

+ 1001

= 1011Which is -3. Simple addition doesn’t work in this case. You need to note that one of the numbers is negative and use a different algorithm if that’s the case. But two’s complement is a clever way of storing integers so that common math problems are very simple to implement. Try adding 2 (0010) and -2 (1110) together and you get 10000. The most significant bit is overflow, so the result is actually 0000.

Additionally, in the “intuitive” storage method, there are two zeroes 0000 and 1000 and we need to take extra steps to make sure that non-zero values are also not negative zero.

There’s another bonus that when you need to extend the width of the register the value is being stored in. With two’s complement, storing a 4-bit number in an 8-bit register is only a matter of repeating its most significant bit until it pads the width of the bigger register.

0001 (one, in 4 bits)

00000001 (one, in 8 bits)

1110 (negative two, in 4 bits)

11111110 (negative two, in 8 bits)Left shift and Right shift

In an arithmetic shift (<< and >>), the bits that are shifted out of either end are discarded. In a left arithmetic shift, zeros are shifted in on the right; in a right arithmetic shift, the sign bit is shifted in on the left, thus preserving the sign of the operand. A left arithmetic shift by n is equivalent to multiplying by 2^n (provided the value does not overflow), while a right arithmetic shift by n is equivalent to dividing by 2^n.

In a logical shift, zeros are shifted in to replace the discarded bits. Therefore, the logical and arithmetic left-shifts are exactly the same, so we only have >>> don’t have <<<. The logical right-shift inserts zeros into the most significant bit instead of copying the sign bit, so it is ideal for unsigned binary numbers, while the arithmetic right-shift is ideal for signed two’s complement binary numbers.

An example of replacing if-branch with some bitwise operations.

// the data is 32-bit int array between 0 and 255

if (data[c] >= 128)

sum += data[c];

// be replaced with

int t = (data[c] - 128) >> 31;

sum += ~t & data[c];Arithmetically shift right by 31, it becomes either all ones if it is smaller than 128 or all zeros if it is greater or equal to 128. (0111 -> 0011 -> 0001 -> 0000 or 1000 -> 1100 -> 1110 -> 1111). The second line adds to the sum either 0xFFFFFFFF & data[c] (so data[c]) in the case that data[c] >= 128, or 0 & data[c] (so zero) in the case that data[c] < 128.

How big is 10 MB anyway?

If you are dealing with characters, it will depend on the charset/encoding.

- An ASCII character in 8-bit ASCII encoding is 8 bits (1 byte), though it can fit in 7 bits.

- A Unicode character in UTF-8 encoding is between 8 bits (1 byte) and 32 bits (4 bytes).

- A Unicode character in UTF-16 encoding is between 16 (2 bytes) and 32 bits (4 bytes), though most of the common characters take 16 bits. This is the encoding used by Windows internally.

What is the average size of JavaScript code downloaded per website? It seems like shipping 10 MB of code is normal now. If we assume that the average code line is about 65 characters, that would mean we are shipping ~150,000 lines of code.

Systems based on powers of 10 use standard SI prefixes (kilo, mega, giga, …) and their corresponding symbols (k, M, G, …). Systems based on powers of 2, however, might use binary prefixes (kibi, mebi, gibi, …) and their corresponding symbols (Ki, Mi, Gi, …).

Btw, the median web page is 2.2MB (2.6MB on desktop).

What is the integer’s limit?

width minimum maximum

signed 8 bit -128 +127

signed 16 bit -32 768 +32 767

signed 32 bit -2 147 483 648 +2 147 483 647

signed 64 bit -9 223 372 036 854 775 808 +9 223 372 036 854 775 807

unsigned 8 bit 0 +255

unsigned 16 bit 0 +65 535

unsigned 32 bit 0 +4 294 967 295

unsigned 64 bit 0 +18 446 744 073 709 551 615In C, the size of an int is really compiler dependent (many modern compilers make int 32-bit). The idea behind int was that it was supposed to match the natural “word” size on the given platform. “Word size” refers to the number of bits processed by a computer’s CPU in one go, typically 32 bits or 64 bits.

JS Number type is a double-precision 64-bit binary format IEEE 754 value, like double in Java. The largest integer value of this type is Number.MAX_SAFE_INTEGER, which is: 2^53-1. (1 bit for the sign, 11 bits for the exponent, 52 bits for the mantissa).

The simplest version between 32-bit vs. 64-bit software is about the amount of memory available to a program. A 32 bit program uses a 32 bit number as a memory address. That means your program can talk about memory up to 2^32 bytes (which is about 4 GB of data), but it has no way of specifying memory past that. A 64 bit program can talk a whole lot more obviously.

Based on the ASCII table, when we store ‘TAB’ and decimal 9 to the memory, they are both stored as “1001”. How does the computer know it’s a ‘TAB’ or a decimal 9?

The computer doesn’t know what type a specific address in memory is, that knowledge is baked into the instructions of your program. When a location is read, the assembly doesn’t say “see what data type is there”, it just says “load this location of memory and treat it as a char”. The value in memory doesn’t know or care what it is being used as.

In JavaScript, the basic binary object is

ArrayBuffer, a reference to a fixed-length contiguous memory area. What’s stored in it? It has no clue. Just a raw sequence of bytes. You cannot directly manipulate the contents of anArrayBuffer, so theUint8Array(a subclass of the hiddenTypedArrayclass) enters saying “treat it like a sequence of bytes, where each byte is a 8 bit unsigned number”.

What is Unicode and UTF-8?

Every letter in every alphabet is assigned a magic number by the Unicode consortium which is written like U+0639. This magic number is called a code point. The U+ means “Unicode” and the numbers are hexadecimal. U+0639 is the Arabic letter Ain. The English letter A would be U+0041. English text which rarely used code points above U+007F. You can see each code point by pasting text in https://unicode.run. How big is Unicode? Currently, the largest defined code point is 0x10FFFF. That gives us a space of about 1.1 million code points. About 170,000, or 15%, are currently defined. An additional 11% are reserved for private use. The rest, about 800,000 code points, are not allocated at the moment. They could become characters in the future.

Unicode corresponds to code points, just numbers. We haven’t yet said anything about how to store this in memory or represent it. That’s where encodings come in. Encoding is how we store code points in memory. It does not make sense to have a string without knowing what encoding it uses. If there’s no equivalent for the Unicode code point you’re trying to represent in the encoding you’re trying to represent it in, you usually get a little question mark: ? or �

The simplest possible encoding for Unicode is UTF-32. It simply stores code points as 32-bit integers. So U+1F4A9 becomes 00 01 F4 A9, taking up four bytes. Any other code point in UTF-32 will also occupy four bytes. Since the highest defined code point is U+10FFFF, any code point is guaranteed to fit.

Unicode Transformation Format 8-bit is a variable-width encoding that can represent every character in the Unicode character set. It was designed for backward compatibility with ASCII and to avoid the complications of endianness and byte order marks in UTF-16 and UTF-32. In UTF-8, every code point from 0-127 is stored in a single byte. Only code points 128 and above are stored using 2, 3, in fact, up to 6 bytes. English is encoded with 1 byte, Cyrillic, Latin European languages, Hebrew and Arabic need 2, and Chinese, Japanese, Korean, other Asian languages, and Emoji need 3 or 4. The MIME character set attribute for UTF-8 is UTF-8. Character sets are case-insensitive, so utf-8 is equally valid.

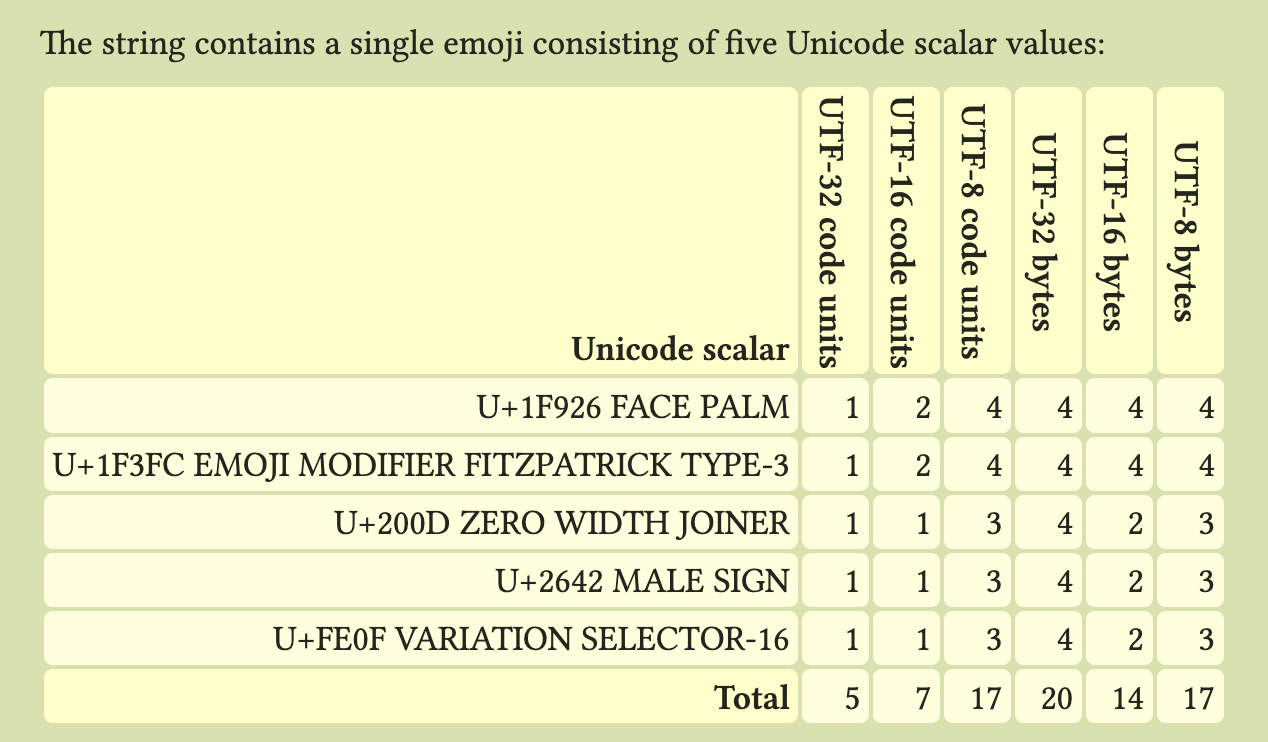

What’s ”🤦🏼♂️”.length? Different languages use different internal string representations and report length in whatever units they store. For example, JavaScript (and Java) strings have UTF-16 semantics, so the string occupies 7 code units.

const str = "Hello, 👋!";

// bug occurs because the `split` method treats the string as an array of 16-bit units.

str.split("").reverse().join("");

// split into an array of actual characters

Array.from(str).reverse().join("");

// or

[...str].reverse().join("");