Pixel, resolution and fps

Concept of pixel and resolution

Pixel is the unit of measurement for digital images. Resolution is the number of pixels on a device found in each dimension (width × height) that can be displayed on the screen. For example, a device with the resolution of “1024 × 768” has a 1024-pixel width and a 768-pixel height. Pixel Density is usually measured in PPI (Pixels Per Inch), which refers to the number of pixels present per inch on the display. A higher pixel density per inch allows for more sharpness and clarity when using the device.

The Retina screen doubled the PPI while keeping the same screen size, meaning the number of pixels that fit into the same space had quadrupled (twice the number of pixels across and twice the number of pixels down). But all the old graphics had to be drawn at the same size on the higher density phone. If the phone had drawn all the graphics at a 1:1 scale like it did originally, everything would have been drawn at a quarter the size in the new screen. To prevent this, Apple started using points as a way of separating the drawing of the graphics from the density of the screen they were on. Points (abstract unit) are equal to different pixels based on PPI. On a standard-resolution screen, 1 point (1pt) is equivalent of 1 pixel (1px). High-resolution screens or Retina displays have a higher pixel density and as a result, 1 point is equal to 2 pixels across and 2 pixels down, or 4 total pixels.

There is a distinction between the physical pixels in a screen and the software pixels we write in CSS. With high-resolution screens, something that is

1pxin our CSS will likely take up multiple physical hardware pixels, and we don’t really have any way in pure CSS to specify a literal device pixel. Every time a user changes their screen’s resolution or zooms in, they’re changing how software pixels map onto hardware pixels.

A standard resolution image has a scale factor of 1.0 and is referred to as an @1x image. High resolution images have a scale factor of 2.0 or 3.0 and are referred to as @2x and @3x images. Suppose you have a standard resolution @1x image that’s 100px by 100px, then the @2x version of this image would be 200px by 200px. The @3x version would be 300px by 300px. (iPhone X, iPhone 8 Plus, iPhone 7 Plus, and iPhone 6s Plus = @3x; Retina displays and all other high-resolution iOS devices = @2x) Their display size in CSS doesn’t change.

There is another issue in the workplace. Look at the number of pixels in the PSDs. The @2x PSD has four times as many pixels. The @3x has nine times as many. Designers have been working @2x or @3x and then begin to spec their design for developers. The developers get a complete spec in which they need to divide everything by 2 or 3.

Window.devicePixelRatio

The devicePixelRatio interface returns the ratio of the resolution in physical pixels to the resolution in CSS pixels for the current display device. This tells the browser how many of the screen’s actual pixels should be used to draw a single CSS pixel. A value of 1 indicates a classic display, while a value of 2 is expected for Retina displays. Other values may be returned as well in the case of when a screen has a higher pixel density than simply double the standard resolution.

/*

`-webkit-device-pixel-ratio` is a non-standard CSS media feature,

which is an alternative to the standard resolution media feature.

*/

@media (-webkit-device-pixel-ratio: 1) {}

@media (-webkit-min-device-pixel-ratio: 2) {}

@media (-webkit-max-device-pixel-ratio: 3) {}

@media (resolution: 150dpi) {}

@media (min-resolution: 72dpi) {}

@media (max-resolution: 300dpi) {}

/*

`image-set()` method lets the browser pick the most appropriate CSS image from a given set,

primarily based on pixel density of the screen and image type.

*/

background-image: image-set("cat.png" 1x, "cat-2x.png" 2x);Viewport meta tag

The browser’s viewport is the area of the window in which web content can be seen. When we started surfing the internet using tablets and mobile phones, fixed size web pages were too large to fit the viewport.

Some mobile devices render pages in a virtual viewport, which is usually wider than the screen, and then shrink the rendered result down so it can all be seen at once. Users can then zoom and pan to look more closely at different areas of the page. For example, if a mobile screen has a width of 640px, pages might be rendered with a virtual viewport of 980px, and then it will be shrunk down to fit into the 640px space. This virtual viewport is a way to make non-mobile-optimized sites in general look better on narrow screen devices.

The viewport meta tag allows you to tell the mobile browser what size this virtual viewport should be. A typical mobile-optimized site contains something like <meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1" />.

requestAnimationFrame

The smoothness of an animation depends on the frame rate of the animation. Frame rate is measured in frames per second (fps). More frames, means more processing, which can often cause skipping. This is what is meant by the term dropping frames. Most screens have a refresh rate of 60Hz (1000ms / 60fps = 16.7ms), it’s useless to perform a repaint if the screen cannot show it due to its limitations. By the way, setTimeout(animFrame, 1000 / 60) is used in old animation libraries.

// normal refresh rate

let last = Date.now();

requestAnimationFrame(function cb() {

console.log("time passed from the last frame:", Date.now() - last);

last = Date.now();

requestAnimationFrame(cb);

});

// long task

document.addEventListener("click", function() {

let now = Date.now();

requestAnimationFrame(() =>

console.log("time passed from the last frame:" + (Date.now() - now))

);

while (Date.now() < now + 1000);

});What’s wrong with creating animations using setTimeout or setInterval? First, the browser might be busy performing other operations, and the setTimeout calls might not make it in time for the repaint, and it’s going to be delayed to the next cycle. This is bad because we lose one frame, and in the next cycle the animation is performed 2 times, causing the eye to notice the awkward animation. Second, the tab is being hidden, or the animation itself could have been scrolled off the page making the update call unnecessary. Chrome does throttle setInterval and setTimeout to max 1 execution per second in hidden tabs, but this isn’t to be relied upon for all browsers.

For scripts that rely on WindowTimers like

setInterval()orsetTimeout()things get confusing when the site which the script is running on loses focus. Chrome, Firefox and maybe others throttle the frequency at which they invoke those timers to a maximum of once per second in such a situation. However this is only true for the main thread and does not affect the behavior of Web Workers. Therefore it is possible to avoid the throttling by using a worker to do the actual scheduling. This is exactly what worker-timers does. It is a replacement forsetInterval()andsetTimeout()which works in unfocused windows.

requestAnimationFrame is a native API for running any type of animation in the browser. Browser vendors have decided, “hey, why don’t we just give you an API for that, and we can probably optimize some things for you.” So it’s a basic API using for animation, whether that be DOM-based styling changes, canvas or WebGL. You don’t need to specify an interval rate, and that all depends on the frame rate of the browser, typically it’s 60fps. The key difference here is that you are requesting the browser to draw your animation at the next available opportunity, not at a predetermined interval. It has also been hinted that browsers could choose to optimize performace based on element visibility and battery status, causing animations to stop if the current window is not visible. Using requestAnimationFrame, it will group all of your animations into a single repaint, and all the animation code runs before the rendering and painting event.

The browser will not render anything while JavaScript is still running.

// Does this cause the element to flash for a brief millisecond?

document.body.appendChild(el);

el.style.display = "none";

// No. All this code takes place before a rendering is ever triggered.

// This all happens within one JS tick,

// before the browser has had a chance to repaint the screen.requestIdleCallback

The window.requestIdleCallback() method queues a function to be called during a browser’s idle periods. This enables developers to perform background and low priority work on the main event loop, without impacting latency-critical events such as animation and input response.

main-thread-scheduling lets you run computationally heavy tasks on the main thread while ensuring your app’s UI doesn’t freeze.

Animations Overview

Modern browsers can animate two CSS properties cheaply: transform and opacity. If you animate anything else, the chances are you’re not going to hit a silky smooth 60 frames per second.

To display something on a webpage the browser has to go through the following sequential steps, and these four steps are known as the browser’s rendering pipeline.

- Style: Calculate the styles that apply to the elements.

- Layout: Generate the geometry and position for each element.

- Paint: Fill out the pixels for each element.

- Composite: Separate the elements into layers and draw the layers to the screen.

When you animate something on a page that has already loaded these steps have to happen again. For example, if you animate something that changes layout, the paint and composite steps also have to run again. Animating something that changes layout is therefore more expensive than animating something that only changes compositing.

By placing the things that will be animated or transitioned onto a new layer, the browser only needs to repaint those items and not everything else. Browsers will often make good decisions about which items should be placed on a new layer, but you can manually force layer creation with the will-change property. However, creating new layers should be done with care because each layer uses memory.

Painting can break the elements in the layout tree into layers. Promoting content into layers on the GPU instead of the main thread on the CPU improves paint and repaint performance. There are specific properties and elements that instantiate a layer, including

<video>and<canvas>, and any element which has the CSS properties ofopacity, a 3Dtransform,will-change, and a few others.

Hardware acceleration is a general term for offloading CPU processes onto another dedicated piece of hardware. In the world of CSS transitions, transforms, and animations, it implies that we’re offloading the process onto the GPU, and hence speeding it up. This occurs by pushing the element to a layer of its own, where it can be rendered independently while undergoing its animation.

- Hardware-accelerated layer compositing is enabled in the browser.

- Only compositing CSS properties (

opacity,transform: translate / scale / rotate, etc) are acceleratable. - The element has been given its own compositing layer. (it may be forced by using a “go faster” hack like

transform: translate3d)

More knowledge about GPU:

Broadly speaking, CPUs are better for sequential programs and GPUs are better for parallel programs. CPUs have a small number of large cores (Apple’s M3 has an 8-core CPU), and GPUs have many small cores (Nvidia’s H100 GPU has thousands of cores).

- GPUs (Graphical Processing Units) were originally designed to accelerate rendering of images, 2D, and 3D graphics. However, due to their capability of performing many parallel operations, their utility extends beyond that to applications such as deep learning. GPUs prioritize having a large number of cores to achieve a higher level of parallelism.

- Imagine you want to add two vectors, a simple implementation iterates over the vector, adding each pair of elements on each iteration sequentially. But the addition of the ith pair of elements does not rely on any other pair. So, what if we could execute these operations concurrently, adding all of the pairs of elements in parallel? That’s when the GPUs come into action. Modern GPUs can run millions of threads simultaneously, enhancing performance of these mathematical operations on massive vectors.

Infinite scrolling performance analysis

Our goal is to create an infinite vertical scroll of two divs (each 100vh tall) that continuously loop, with div 1 smoothly following div 2 to create a seamless experience.

The performance issues of changing scrollTop with requestAnimationFrame:

- Each frame requires DOM writes (

scrollTop +=), which can trigger layout recalculations. - The

scrollTopmanipulation can cause browser repaints, especially with large content. - If the main thread is busy,

requestAnimationFramecallbacks may be delayed.

<style>

.container {

height: 100vh;

overflow: hidden;

}

.scroll-wrapper {

animation: scroll 10s linear infinite;

will-change: transform;

}

.div-box {

height: 100vh;

}

.div1 { background-color: #3498db; }

.div2 { background-color: #e74c3c; }

@keyframes scroll {

0% {

transform: translateY(0);

}

100% {

transform: translateY(-200vh); /* Total height of all original divs */

}

}

</style>

<body>

<div class="container">

<div class="scroll-wrapper">

<!-- Original divs -->

<div class="div-box div1">1</div>

<div class="div-box div2">2</div>

<!-- Cloned divs for smooth infinite scrolling -->

<div class="div-box div1">1</div>

</div>

</div>

</body>Advantages of CSS Solution:

- CSS transforms (

translateY) are hardware-accelerated by default. will-change: transformfurther optimizes by offloading animation to GPU.- No layout recalculations during animation.

When the UI freezes, if you’re wondering why the rotating icon keeps spinning even when everything else is frozen, that’s a neat detail! CSS animations (like

transform: rotate) are handled by the browser’s compositor thread, not JavaScript, so they continue running smoothly even when the main thread is blocked.

So instead of asking yourself, “How can I write code that does what I want?” Consider asking yourself, “Can I write code that ties together things the browser already does to accomplish what I want?”

Best practice for font units

1pxis equal to whatever the browser is treating as a single pixel (even if it’s not literally a pixel on the hardware screen).1remis always equal to the browser’s font size — or, more accurately the font size of thehtmlelement.1emis the font size of the current element, andfont-size: 1emis equivalent tofont-size: 100%.

When you zoom, everything gets scaled up (or down), and in that scenario, the choice of px or em/rem as your CSS unit doesn’t generally matter. It essentially applies a multiple to every unit, including pixels. But zoom isn’t the only way users make websites more usable for themselves, changing the default font size in the browser settings will redefine the default font size that all relative units will be based on (rem, em, %).

On the web, the default font size is 16px. Some users never change that default, but many do. Remember, px values do not scale up or down when the user changes their font size, but em and rem values do adjust in proportion to font size. So asking yourself: “Should this value scale up as the user increases their browser’s default font size?” If the value should increase with the default font size, use rem. Otherwise, use px.

CSS Length Units: https://codesandbox.io/embed/length-units-mcilvb

- Absolute (1in, 1px, 1pt)

- Relative to font (1em, 1rem, 1ch, 1lh)

- Percentage of viewport (1vw, 1vh, 1vmin, 1vmax, 1dvw, 1dvh)

- Container query (1cqw, 1cqh)

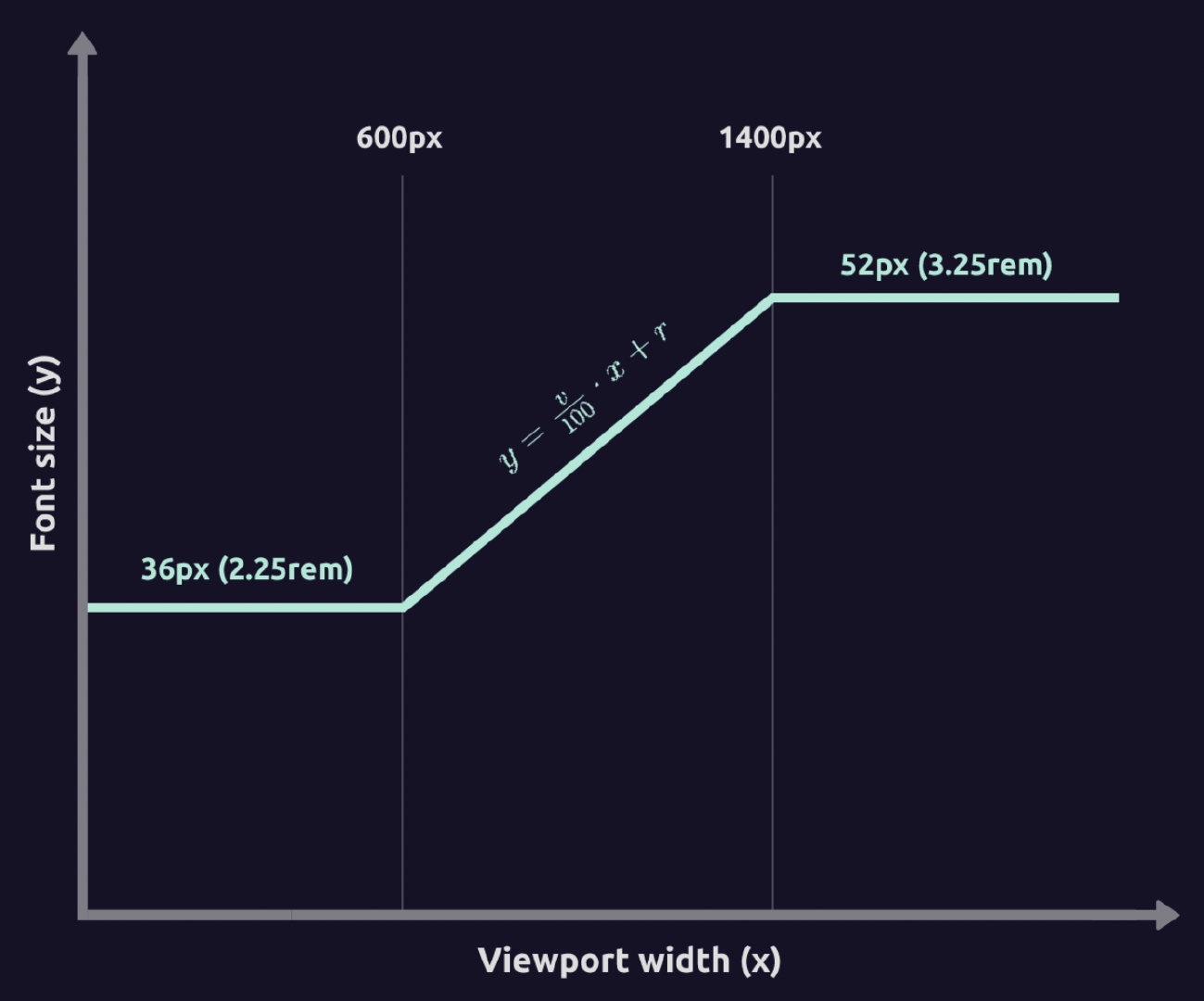

Fluid typography

https://www.smashingmagazine.com/2022/01/modern-fluid-typography-css-clamp

Use CSS clamp() to make any property have min + max values:

If we want to define a default value and both a minimum and maximum value, we could use width: max(300px, min(90%, 700px));, and there’s a handy alternative for this, width: clamp(300px, 90%, 700px);, meaning the width of the element is 90% with a minimum width of 300px and maximum width of 700px.

/* Fixed minimum value below the minimum breakpoint */

.fluid {

font-size: 36px;

}

/* Fluid value from 600 to 1400px viewport width */

/*

font-size: calc([value-min] + ([value-max] - [value-min]) * ((100vw - [breakpoint-min]) / ([breakpoint-max] - [breakpoint-min])));

*/

@media screen and (min-width: 600px) {

.fluid {

font-size: calc(36px + 16 * ((100vw - 600px) / (1400 - 600)));

}

}

/* Fixed maximum value above the maximum breakpoint */

@media screen and (min-width: 1400px) {

.fluid {

font-size: 52px;

}

}Use the formula y = (v / 100) * x + r to calulate clamp([min]rem, [v]vw + [r]rem, [max]rem), which has the same effect as the code in above Fluid Typography but in one line and without the use of media queries.

- y — resulting fluid font size for a current viewport width value x (px).

- x — current viewport width value (px).

- v — viewport width value that affects fluid value change rate (vw).

- r — relative size equal to browser font size. Default value is 16px.

/*

* We have two equations with two parameters that we need to calculate — viewport width value v and relative size r.

v = (52 - 36) / (1400 - 600) * 100 = 2vw

r = (600 * 52 - 1400 * 36) / (600 -1400) = 24px = 1.5rem

*/

.fluid {

font-size: clamp(2.25rem, 2vw + 1.5rem, 3.25rem);

}